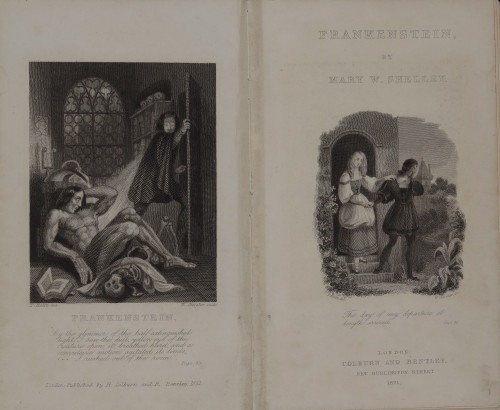

In 1831, a newly revised edition of Mary Shelley’s thriller Frankenstein; or, The Modern Prometheus was published in London — now, for the first time, with an illustration. It depicts the dramatic moment in which the artificial creature awakens to life and its creator Viktor Frankenstein flees in horror. The artist was the Briton Theodor von Holst, who here adopted elements from his Faust illustrations.

The first edition had come out in 1818 — anonymously. Shelley had written it in 1816 at the Villa Diodati on Lake Geneva. A clique of British poets had gathered at the estate in what would prove to be a cold and thunderstorm-ridden summer. Lord Byron and his doctor John Polidori were there, along with Percy Bysshe Shelley, his lady-love — and later wife — Mary Godwin, and her younger sister Claire Clairmont. They whiled away the time with intoxicants and horror stories from Germany, which they read in French. Thus inspired, they decided to have a contest for who could write the best ghost story. It was a woman — the eighteen-year-old Mary Shelley — who ran rings around the male writers of the bunch. Her Frankenstein; or, The Modern Prometheus is a modern myth of creation born of the Romantic spirit. Like the ancient figure Prometheus, who forms human beings from clay and gives them the fire of the gods, Shelley’s Frankenstein is a scientist who, driven by his thirst for knowledge, unscrupulously creates a new human being from parts of corpses. His creature will become the paradigm of the scary monster although he has a well-developed mind, learns to read, and edifies himself with Goethe’s Sorrows of Young Werther and other works. The author also incorporated recent scientific discoveries such as electricity and galvanism into her text. The story raises a question that has lost nothing of its relevance to this day: Can a scientist decide, like God, to give life and take it away?

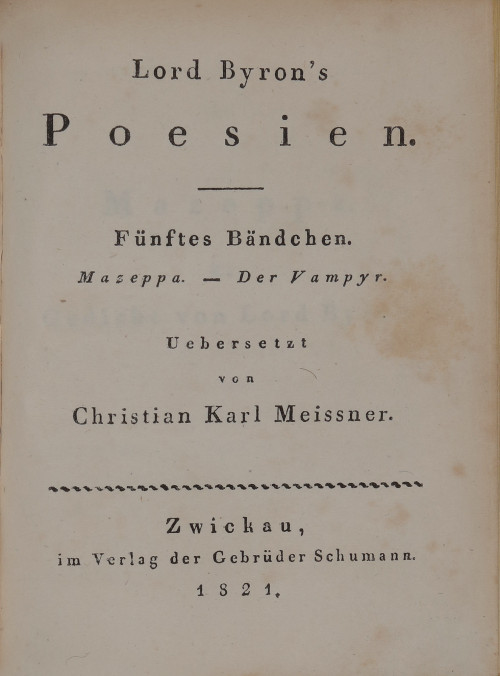

A tale entitled The Vampyre also had its origins in the productive atmosphere on Lake Geneva. The author was not Byron, but his doctor, Polidori, who thus invented a new type of vampire modelled after the image the public had of Lord Byron: an aristocratic seducer, as attractive as he is terrifying, indefatigable, and untied to any place.

In 1819, Polidori’s story came out in a magazine — without his prior knowledge. What is more, the publisher, hoping to increase his revenues, cited Byron as the author. The false attribution gained lasting credence, even though both authors sought to put the record straight. However, it didn’t do the tale’s popularity any harm. On the contrary, even Goethe referred to the book as “Byron’s best product”.

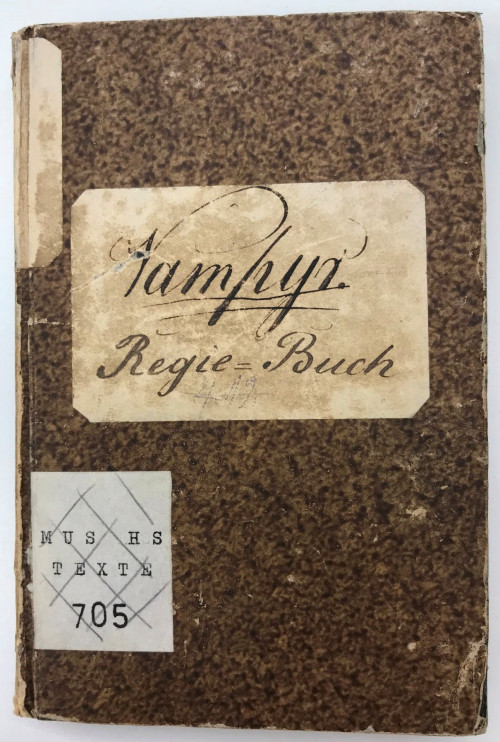

In 1828, the composer Heinrich Marschner staged the Vampyre as a Romantic opera. The display case features the promptbook for the 1832 stage production in Frankfurt. Yet Mary Shelley and John Polidori’s monsters conquered not only the theatre, but also the cinema — a fact to which the excerpts in the video installation in the next room testify. To this day, film adaptations like these still shape our images of, for example, the Frankenstein monster and his awakening to life by the famous bolt of lightning — a scene that doesn’t even occur in Mary Shelley’s novel.

Objects

-

MARY SHELLEY

Frankenstein: or, The Modern Prometheus. By the Author of The Last Man, Perkin Warbeck

Revised, Corrected, and Illustrated with a New Introduction, by the Author. London: Colburn and Bentley; Edinburgh: Bell und Bradfute; Dublin: Cumming 1831 (Bentley’s Standard Novel 9). 3. Ausgabe. Frontispiz und Titelvignette von Theodor von Holst.

-

HEINRICH MARSCHNER

Der Vampyr. Romantische Oper in zwei Aufzügen. Nach Lord Byron’s Erzählung frei bearbeitet von Wilh. Aug. Wohlbrück, Regisseur des Magdeburger Theaters. In Musik gesetzt von Heinrich Marschner, Königl. Sächsischem Musik-Direktor

Leipzig: Hartmann 1828.

-

JOHN WILLIAM POLIDORI

Lord Byron’s Poesien. Fünftes Bändchen. Mazeppa. – Der Vampyr

Zwickau: Schumann 1821.