Karoline von Günderrode was one of the most unusual women writers of her time. Her longing for freedom was nearly impossible to reconcile with the conventional role assigned to women. The well-read author did not confine herself to the usual themes and genres considered becoming to a woman in her day. As a result, many of her contemporaries considered her work a “strange phenomenon”, as Goethe put it.

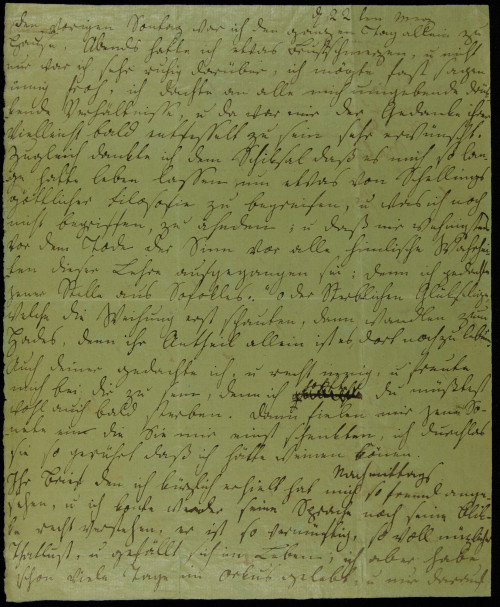

In the summer of 1804, Günderrode made the acquaintance of Friedrich Creuzer, a man nine years her senior. He was a classical scholar who taught in Heidelberg. The two shared an interest in classical literature and the study of the myths. They soon fell in love, but Creuzer was bound by a marriage of convenience. Their secret relationship — or “covenant in life and death”, as Günderrode called it in the letter of March 1805 here on view — thus remained in a state of constant vacillation between hope and disappointment. When Creuzer broke with her in a letter the following year, she was sojourning in Winkel on the Rhine. And it was there that she took her own life, stabbing herself in the heart with a dagger.

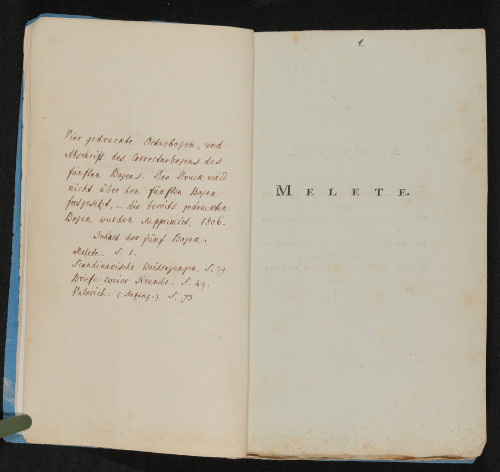

At that point in time, Günderrode’s last work was about to go into print. It was Melete, which Creuzer had prepared for publication. Under the title Letters of Two Friends, it also contained a two-way correspondence whose writers were identifiable as the author and Creuzer. In keeping with the advice of a friend and the wishes of Günderrode’s brother, Creuzer stopped the printing process. A single copy survived and is here on view in the display case. It contains four proofs; the fifth was transcribed by Fritz Schlosser, from whose estate this copy came to us.

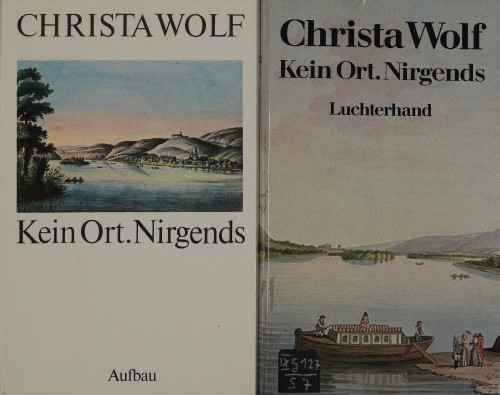

In the twentieth century, Karoline von Günderrode became known to a broader public through the writer Christa Wolf. In her book No Place on Earth, published in 1979, Wolf describes a fictional encounter between Günderrode and Heinrich von Kleist. The two of them converse about the limits to the possibilities for self-fulfilment within the confines of bourgeois reality, and about the scope offered by poetry.

Next to the display case containing Günderrode’s letter to Creuzer is a second case containing a letter from Heinrich von Kleist. Several years before he likewise took his life, he wrote to his fiancée Wilhelmine von Zenge, who had declared her refusal to join him in a simple rural existence. In the letter, he broke off contact to her with the following words: “Dear girl, do not write to me again. I have no other wish than to die soon.” Both letters are expressions of disappointed expectations — not only in love.

Are you thinking about taking your own life? Do you have the feeling you don’t know how to go on? Here you can find help in seemingly hopeless situations: https://www.befrienders.org/need-to-talk

Objects

-

WOLFGANG RIHM

An Creuzer, 1990

Aus „Das Rot. Sechs Gedichte der Karoline von Günderrode“. Clare Lesser (Sopran), David Lesser (Klavier). Metier 2013

-

KAROLINE VON GÜNDERRODE

Melete, 1806

-

KAROLINE VON GÜNDERRODE

Letter to Friedrich Creuzer, Frankfurt a. M., March 22, 1805

-

Schnürriemen

-

JACOB WILHELM CHRISTIAN ROUX

Friedrich Creuzer, um 1820

-

HEINRICH VON KLEIST

Letter to Wilhelmine von Zenge, Thun, May 20, 1802

-

KAROLINE VON GÜNDERRODE

Edle Freundschaft nur verbindet, 1794

-

CHRISTA WOLF

Kein Ort. Nirgends

Berlin, Weimar: Aufbau-Verlag 1979. Darmstadt, Neuwied: Luchterhand 1979.